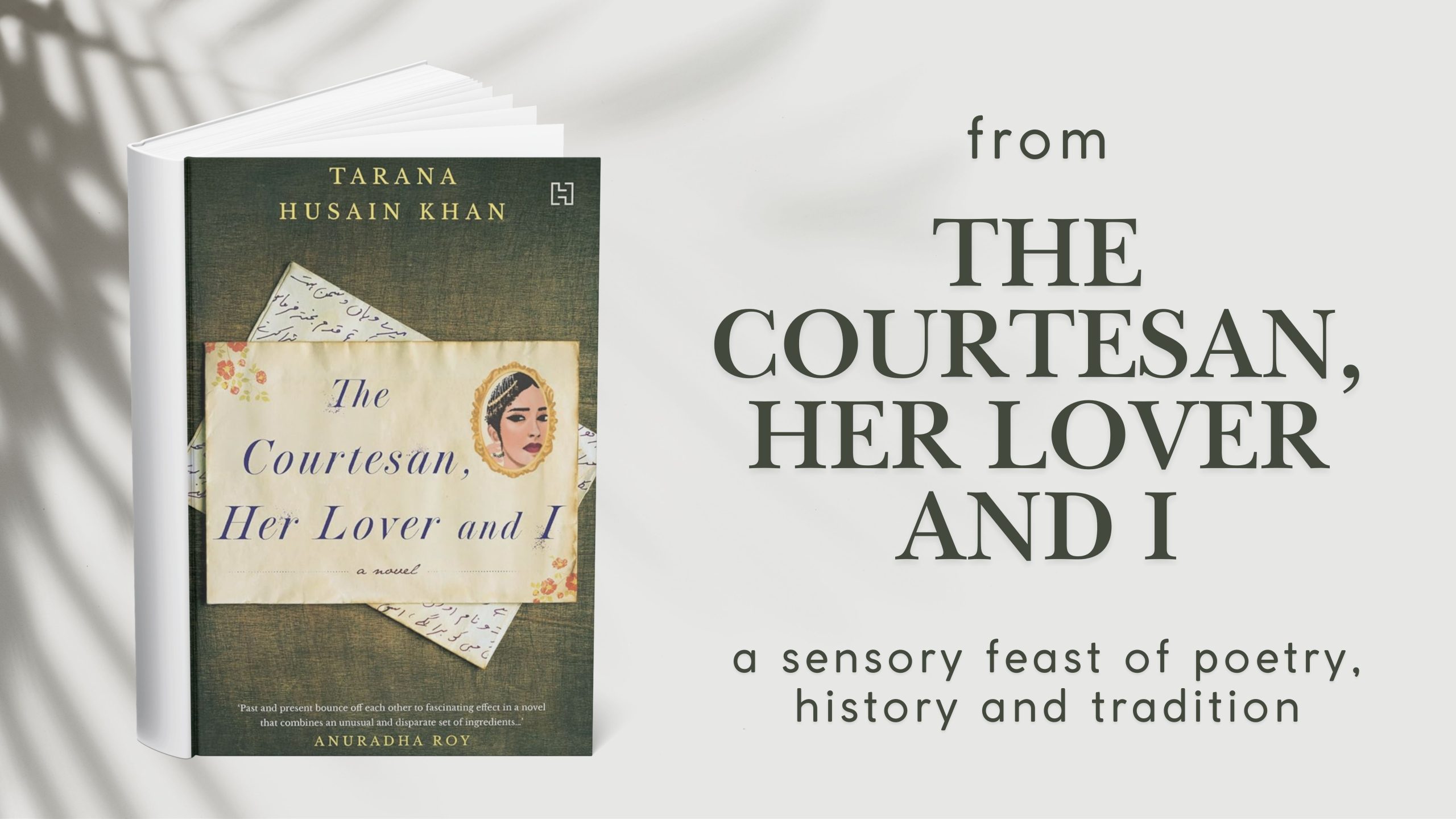

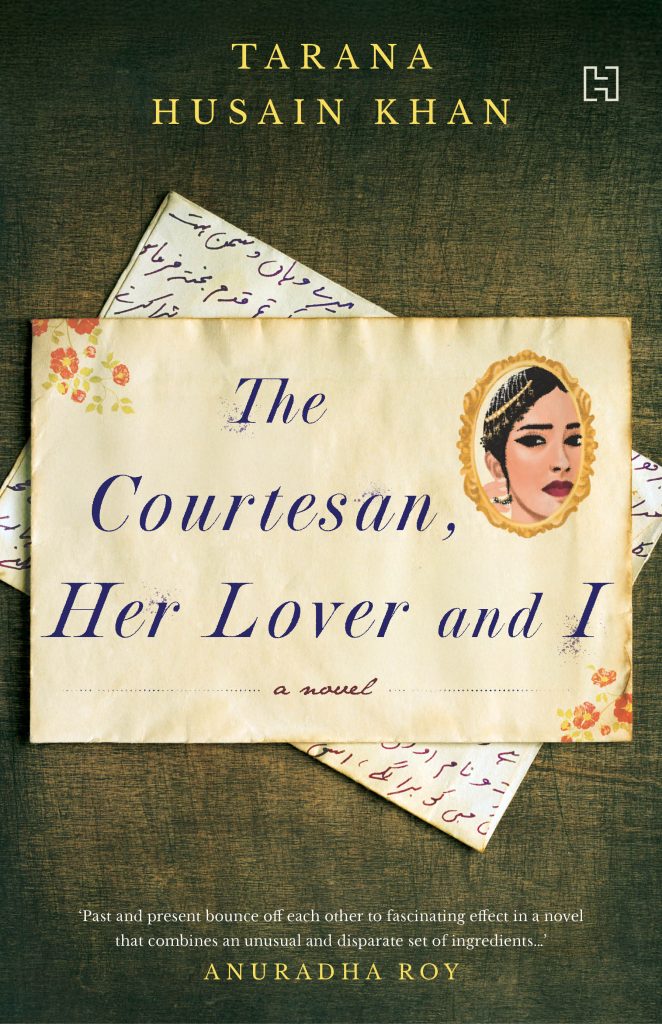

From The Courtesan, Her Lover and I: a Sensory Feast of Poetry, History and Tradition

- February 9, 2026

- Publishing

Hijab, at nineteen, you had achieved more than an ordinary woman could aspire to—a beautiful tawaif, a published poetess, with a diwan to your name, you were perched on the precipice of fame. A new century was about to begin; the stories of mutiny against the angrez, the lived histories of the apocalyptic revolt of 1857 against British rule—vivid narratives by Apa, your mother, and Khala, your aunt—were all in the past now. The survivors, displaced and ravaged, had fashioned new ways to live out their lives. Company Raj, the rule of the East India Company, was over, and the rotund and remote British queen ruled from ‘Englistaan’. The world, resurrected and new, lay at your feet. Even the esteemed tawaif, Malka Jan, noticed you and had invited you to her daughter Gauhar’s birthday celebration at her grand Chitpur Road residence. Malka Jan, half-European, with her impossibly fair complexion coveted among Indian tawaifs, reigned over Calcutta with her words and music.

‘Malka Jan is a half-breed, and her mother, a Hindu, had left the profession to become the bibi of a white man, only to return to it after he divorced and discarded her. I think Malka just wants to see the competition; be careful of her,’ Apa had snorted. You were a khandani courtesan, shaped by generations of women honing their art, folding heritage into layers of their dupattas and the beat of their anklets. Blood, art and coquettish adas passed on from mother to daughter.

Malka Jan, once your neighbour in Colootola—though she didn’t visit your family then—had bought a two-storied house in upmarket Chitpur Road for an exorbitant 40,000 rupees just three years after moving from Banaras with her little daughter, Gauhar. This move was a symbol of her newly minted grandeur, an attempt to rewrite herself. She had started learning the trade but lacked the maturity of ancient tawaifs. Apa was right—you could sense Malka Jan’s tremulous jealousy flickering beneath her effusive compliments. She was just a few years older than you at twenty-five but, as Apa said, motherhood ages a woman by years. You and your sister called your mother Apa, elder sister, instead of Ammi—a custom in your community to evade the aging mantle of motherhood. Still, it was thrilling to be recognized by Malka Jan as competition. You complimented her in turn and told her that you had memorized all her ghazals.

‘This is where I will live one day,’ you told your sister, Hameedan, on your way back. Your Colootola house, overlooking the bustling bazaar, seemed diminished and insipid despite the carpets, mirrors and chandeliers acquired over the years. Apa had bought the house after years of struggle for survival and recognition in Calcutta. She was one of the many tawaifs displaced after the violent suppression of the rebellion in Awadh. Initially, she bought the first floor and set up her salon there. There were just three rooms around the hall, which she used for her soirées. A balcony with wrought iron railing overlooked the street below. Later, as the girls grew up, Apa bought the upper floor from an old tawaif, and you, with Hameedan, Apa and Khala, moved to that floor The lower rooms were set up with ornate furniture and chandeliers to entertain clients. The Colootola area was known for Muslim tawaifs from Awadh and north India, and Apa was happy to be there because she could still hear Awadhi and Allahabadi dialect on the tongues of old tawaifs; but it was plebeian, almost vulgar compared to Chitpur with its grand colonial buildings. Malka Jan’s house, nestled next to the Nakhuda Mosque, was a mere turn and a short walk from your house but a world away. You would find your way there soon, you decided.

An invitation from Haider Ali Khan to present your ghazal at the Benazir Mela, the spring festival held at the princely state of Rampur, arrived in answer to your ambitions. A renowned patron of art and music, Haider Ali Khan, the brother of Nawab Kalb e Ali Khan of Rampur, was enthralled by your kalaam and your reputed beauty and voice. Flattered and ecstatic, you accepted the invitation. Apa said travel was the path to refinement for tawaifs and well-travelled courtesans drew rich and discerning patrons.

The train journey from Howrah to Lucknow was your first experience of train travel. Apa, Khala, Hameedan and your brother, Khuda Bakhsh, travelled with you along with four accompanists. Khala’s son, Shafeeq, had been entrusted to look after the kotha with Maulvi Sahib, your old Urdu tutor, and his wife. Large columns of nashteydaans clanked with the richness of kababs, qeema, be-pani ka gosht, khade masaley ka gosht, stacks of roghani tikiya and puris; steel canisters filled with water were hauled into the compartment along with tin suitcases and bedding rolls. Khala, the master cook of the family, had prepared all the dishes in ghee with barely any water so that the food would be preserved through the long travel. Khala and Apa knew the secret Awadhi recipe of be-pani ka gosht—preparing meat curry without a drop of water. ‘Three parts curd, four parts meat and ghee, and not even a drop of water —remember this, girls. You won’t get to eat it after I die,’ Khala said, claiming that it would remain fresh for fifteen days in summers and two months in winters. She said the secret was preparing the meat using a lot of thick curd and ghee and cooking it on low heat for hours. You loved the thick, rich curry of be-pani ka gosht, the perfect balance of sharp spices, tangy curd and the light sweetness of fried onions. You never ate the tender meat pieces, just gorged on the curry with parathas. The dish was associated with picnics near the Hooghly and rare excursions to the hills. Apa always got food prepared in Awadhi style, which she said was the best cuisine in the world. She was dismissive of Bengali food, saying the Bengalis didn’t know the fine art of cooking till Nawab Wajid Ali Shah came with his khansamas and educated them. Awadh lived in her heart as the culture capital of Hindustan.

Excerpted with permission from The Courtesan, Her Lover and I by Tarana Husain Khan. Published by Hachette India.